DOCUMENT: Costa-Gavras' STATE OF SIEGE (dir by Costa Gavras, written by Franco Molinas & Costa-Gavras, with Yves Montand, France/Germany/Italy, 121mns, 1972)

Movies like Costa-Gavras STATE OF SIEGE and Z are part of a high watermark for political cinema from the mid 1960's through the late 1970's. Filmmakers like Gavras, Francesco Rosi, Fassbinder, Paddy Chayevsky among many others were making movies that met the moment head on.

While many (if not almost all) of the moviemakers' political sentiments lean left, there is still a journalistic rigor and clarity that defines this era's work. Agree or disagree with the implied conclusions, viewers almost always feel like they understand better the situation, the stakes, and the moving parts of these complex political moments.

These movies challenge us. Never have such political movies been more necessary than our current moment. Who will stick their neck out to try and document and understand the world-shaking events occurring right now?

Greek-French moviemaker Costa-Gavras made several masterpieces in the political genre. Z, his 1968 masterwork, deals with the assassination of a Greek dissident and its aftermath. MISSING delved into the secret murders and police abuses in the Pinochet-dictatorship of Chile in the 1980's.

STATE OF SIEGE fictionalizes the real-life story of US official Dan Mitrone. Here USAID worker Philip Michael Santore (Yves Montand) is kidnapped by Uruguayan political revolutionaries in a gambit to get political prisoners released. The back and forth of the week shows that Santore's and the government's fate hang in the balance.

Just like Z, SIEGE snaps, crackles, and pops with jittery, propulsive cinematic style. The movie starts at the end so the question of how this all played out is never in doubt. Instead the movie, like many in the genre, becomes a journalistic examination of the facts cinematically. A cine-invrstigation as Rosi called it. There's a point of view to be sure. But there's also an integrity so we understand the forces at work.

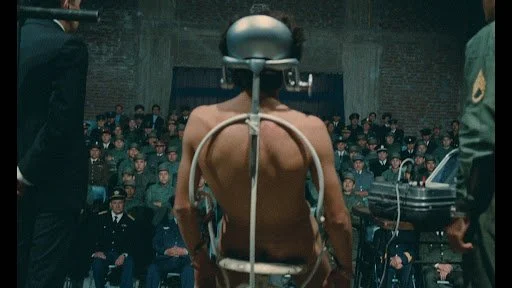

Revolutionaries (known as the Tupamaros) kidnap three high ranking foreign officials including USAID worker Philip Michael Santore. We then cross cut between Santore's interrogation at the hands of a skilled Tupamaro with the government's negotiation to get Santore released to the media's reporting across the week.

The interrogation scenes are didactic but truly communicate detail, info, geopolitical context. Not something all didactic scenes actually are able to do…

Bit by bit, we learn that Santore is actually a Covert Ops instructor in military and police interrogation methods that include torture. Smuggled into South American countries like Uruguay under benign titles like "Transportation Advisor", instructors like Santore are working to strengthen right-wing governments to prevent or suppress Communist/Socialist/Anarchist resistance groups.

It's strange at first to listen to everyone speaking French in a movie about a South American Spanish-speaking country centered on a US covert operator. But you get over that quick when you remind yourself American movies do this kind of thing all the time.

The movie tends towards didacticism, as gripping as it is, because it uses the Santore interrogations more as a way to communicate US foreign policy practices in Central and South America rather than to advance drama. AND, the movie's clear sympathies with the resistance movements do color the conclusions. As a viewer, you have to remind yourself the revolutionaries were likely never this calm, reasonable or without huge flaw.

The torture tactics taught to military governments to suppress supposedly threatening terrorist groups is a reminder that even if the threat is real in some way, the “remedy” may make everything much worse and solve nothing.

This partisanship is often the achilles' heel of these movies. Only moviemakers like Rainer Werner Fassbinder or Paul Verhoeven seem to think things through enough to show the "warts and all" reality of how things probably are.

Still, Costa Gavras is dedicating a movie to historical and political facts. Powerful countries-specially the US and the USSR-have meddled in the internal governments and politics of countless countries causing damage, trauma, murder, death, destruction that reverberate to this day.

Like Graham Greene's Vietnam novel, THE QUIET AMERICAN, STATE OF SIEGE shows how an American "advisor" in the 20th century was often a police and/or military trainer/organizer there to crush dissent.

These inconvenient truths and the lessons of interference haven't fully been absorbed. Certainly, countries must engage and work to develop influence, trust, sway with other countries. And certainly geopolitics is a cold game that can't be played by naive idealists, ideologues, dogmatists, and fanatics (and yet often is).

STAGE OF SIEGE is a dynamic movie made dynamically. This is Costa-Gavras' secret sauce at this point in his career. He illuminates something that must be brought out into the open in a cinematic and engaging way.

If the movie's politics are ultimately too simplistic, its basic thesis still feels spot on: disguised meddling in other country's internal affairs, far from providing a durable solution, will often lead to spiraling violence and retribution and instability. At the very least, a cycle of tit for tat that does anything but resolve the problem.

Craig Hammill is the founder.programmer of Secret Movie Club