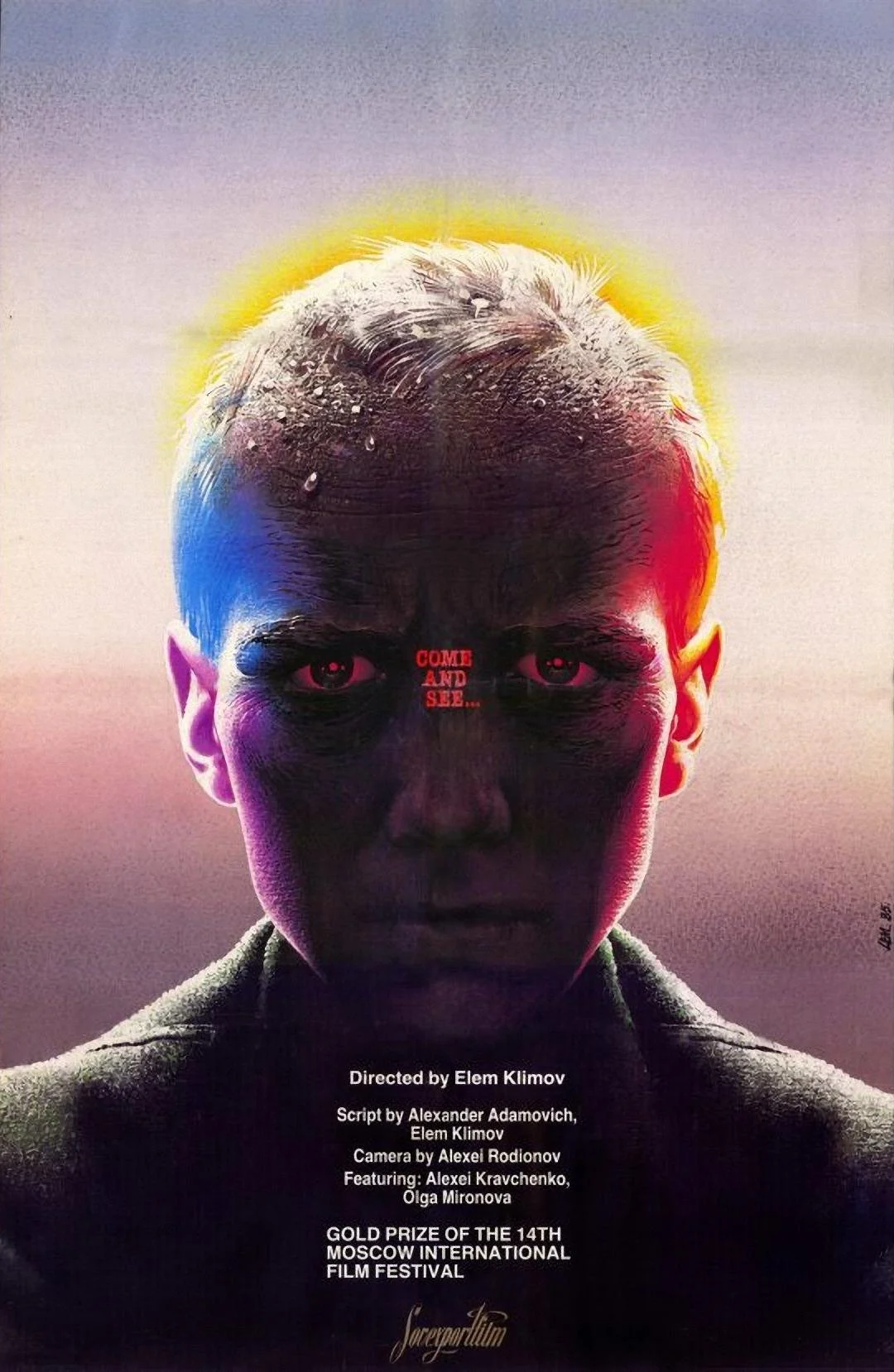

THE END OF ALL THINGS: Elem Klimov's COME AND SEE (co-wri & dir by Elem Klimov, starring Aleksei Kravchenko, 142mns, Belarus/USSR, 1985)

Sometimes a single movie can elucidate and illuminate a country's or region's national character better than a dozen history courses.

At the same time, the viewer must have the humility to realize they will never understand. Not really.

Elem Klimov's World War II horror phantasmagoria COME AND SEE stuns and shocks. It pummels and provokes. It speaks the truth in the blasphemous tongue of experience.

It follows naive if well meaning young Belarusian teen Flyora (a towering performance by Aleksei Kravchenko) as he leaves his mother and sisters to join the partisan resistance movement against the invading Nazis.

He wants to be part of the war effort. He is. But mostly as a horrified witness to the depravity and unconscionable primal horror of man at war.

The movie is a kind of picaresque tale in hell. Florya stumbles from one atrocity to another, unable to really affect any change. But he sees. He sees.

Klimov's style is a delicate mix of terror and poetry. And in this, it's very much of a piece with much of Soviet cinema.

At first, Come and See feels like it might be more of a Terence Malick type tone-poem. But if it is, it’s a near unbearable poem from hell itself.

Watching this movie and what the Belarusians endured at the hands of the invading Nazis (over 600 villages were burned to the ground; the villagers massacred or burned alive), a viewer dimly understands the kind of hardened, unforgiving, real politik character that must arise out of this furnace of trauma, abuse, rape, mass murder.

The movie is a series of stunning sequences. Florya returns home early to discover his entire village slaughtered. Later, in an effort to atone and contribute, Florya embarks with three other men to get food and provisions for starving peasants only to find himself in the middle of a firefight in the fog with a stolen cow.

Naivete gives way to horror which gives way to the unimaginable.

Klimov also acclimates you to the unspeakable. The first hour or so of the movie, while punctuated with grand guignol grotesqueries, is surprisingly lyrical. But the second hour and final twenty minutes become an ever escalating parade of unspeakable tragedy.

Klimov and actor Kravchenko communicate something delicate and profound. Because young teen Florya fails so completely to repel the Germans as a partisan, he comes to feel everything that happens to his village, his people is his fault. This is a common feeling among children who have suffered trauma. That Klimov revolves so much of his movie around this delusional crushing emotion is a center of gravity that informs our own inability to stop the atrocities we witness on screen.

Unlike a moviemaker there to shock just for shock's sake, Klimov is getting at some very deep seated repressed anguish of any people who can't save, stop, prevent the butchery of a psychotic nation mad with war.

The near to final sequence-a sudden blitzkrieg montage in reverse of Hitler's rise returning to a photo of the dictator as a baby on his mother's lap-asks the unanswerable question: if we were to have killed Hitler as a baby would World War II have been avoided?

Ultimately Florya’s role in the resistance is to bear witness. Something almost no human being could do and stay sane.

Whatever Klimov's conclusion, this writer thinks sadly no. Some kind of world conflagaration would have still occurred. The history of humanity is a history of war, mass murder, rape, idealism that curdles into psychosis, and cruelty beyond the ken of the average person.

Paradoxically, this writer still believes humans are basically good.

A movie like COME AND SEE forces you to bear witness, like Florya, to the limitless capacity for atrocity inherent in humanity. And yet there is also a resilience and power to resist and fight such horror.

That Klimov ends the movie with a scene scored to Mozart's REQUIEM which ends in the chorus singing "Amen" as the final word of the movie somehow gets at this paradox better than most forms of trying to communicate the same ineffable mystery.

Craig Hammill is the founder.programmer of Secret Movie Club