HITCH AT THE SUMMIT: NORTH BY NORTHWEST & VERTIGO by Craig Hammill

When Hitchcock made 1958’s Vertigo and 1959’s North by Northwest back to back, one could argue he was at the peak of his powers.

Between 1951 and 1963, Hitchcock directed 13 feature films, none of them bad or even mediocre, all of them good to all-time classic level AND shepherded a television show Alfred Hitchcock Presents among other endeavors (including vinyl albums, mystery books, etc) to great success.

This is the era where Hitchcock made himself an industry. And that’s not written disparagingly. In the brutal ever-changing climate of American movie making, Hitch was smart to become a household name. It allowed studios to view Hitchcock as bankable as the stars in the movie.

In a way, Hitchcock was finally reaping the fruits of 30+ years of hard labor: a Hitchcock movie or TV show was now a genre unto itself. And this gave Hitchcock greater power in choice of story, budget, creative control.

Vertigo is an ode to Hitchcock’s obsessive eye for the importance of detail.

What’s fascinating here is that Vertigo, at the time of its release, was received with a relative commercial and critical shoulder shrug. There was a lot of head scratching. Some thought Hitchcock had been too indulgent in his own style and had forgot the narrative tension and torque that powered his most successful movies.

The ascendance of Vertigo as many filmmakers’ and critics’ favorite Hitch only happened after the moviemaker’s death with the 1982 BFI Sight and Sound Poll. In 2012, Vertigo became the first movie to knock Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane off the #1 perch Kane had occupied for over half a century.

But at the time of its release, Hitchcock, the critics, the box office, the audience all seemed to feel Vertigo had been something of a misfire.

Hitch’s next movie 1959’s North by Northwest was an audience favorite and hit when it was released and has remained so up to this present moment. The movie does feel like a trademark Hitchcock reset (a la The Man Who Knew Too Much 1934, Strangers on a Train, Dial M For Murder, and Frenzy). When Hitch had made a misfire or two, as interesting as they may have been, he understood the game well enough to know he needed a box office success to stay strong in the game.

What’s fairly unique with Hitchcock’s “one for them” or reset movies is that they are often as uncompromising, fascinating, and artistically successful as if Hitch DID NOT NEED to make them to appease the box office Gods. The Coen Brothers’ share this strange ability as well in that Fargo and No Country For Old Men also feel like re-set movies after relative misfires yet ALSO are clearly some of the best movies the Coens ever made.

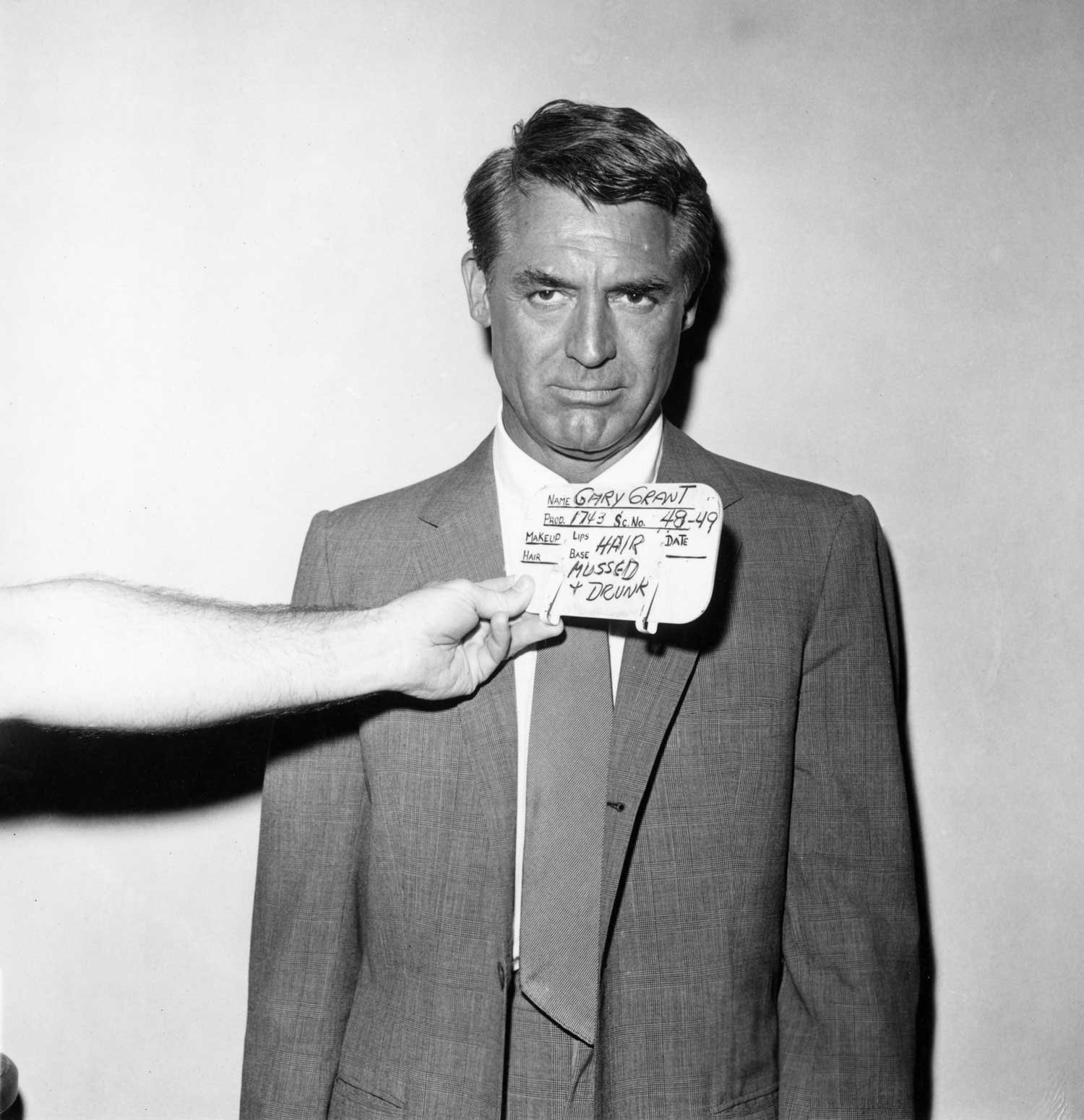

It’s hilarious that this is Cary Grant “drunk and mussed”. He still looks fabulous.

North by Northwest is essentially The 39 Steps in America and Hitchcock has said as much. Much as Steven Spielberg returned to his Duel formula twice (in 1975’s Jaws and 1993’s Jurassic Park), Hitchcock made several variations on his 1935 hit The 39 Steps. His 1942 Saboteur feels like a wonderful first draft of North by Northwest just as his 1948 Rope feels like a wonderful first draft for Rear Window. In fact, both Saboteur and North by Northwest even end with climaxes on American landmarks (the Statue of Liberty in 1942, Mount Rushmore in 1959).

What feels so essential about the proximity of Vertigo and North by Northwest in their filmmaker’s body of work is how well they work as bookends or terrestrial poles to the spectrum and diversity of Hitchcock’s work. Vertigo is exactly the kind of risky experiment and departure that Hitchcock thrilled at throughout his career. Hitchcock made so many movies at such a regular clip that one has to imagine he NEEDED challenges to keep the process exciting, thrilling, and fresh. Vertigo is also one of the rarest of Hitch’s that has a completely devastating, mysterious, bleak dark ending.

One of hundreds of unsettling mysterious shots in Vertigo.

The studio even forced the director to shoot a final scene that was marginally more upbeat: Scottie (Jimmy Stewart) has returned to the apartment of Midge (Barbara Bel Geddes) while they listen on the radio that Gavin Elster has been caught. BUT. . .Hitch refused to use this ending in the picture. And this points to Hitchcock’s commitment to narrative clarity and integrity as much as anything else. One has to imagine Hitchcock, with all his commercial prowess, knew the studio suggested ending would make the bitter pill of Vertigo go down better. But Hitchcock the artist also knew that kind of ending would mar the entire effect of the picture (which builds to the final devastatingly ironic scene atop the church bell tower). The effect would be a fascinating, mysterious, unsettling painting botched by three primary color stripes down the middle.

One of the most tortured romances ever put to screen.

North by Northwest , on the other hand, feels like Hitchcock having a blast doing what he does best-and trying to do it just little better than he has ever done it before. This escapist gem does feel like one of Hitchcock’s most surest sleights of hand. Because every time this writer sees the movie, there are more and more implausible elements that raise questions. Why would the spies go to such lengths to have Cary Grant’s Thornhill killed by a cropduster? Why would they take over the house of a United Nations diplomat and not get caught? How is it believable that James Mason’s main spy somehow has a modernist house just behind Mount Rushmore? And that planes somehow land and leave from this house to go to foreign countries to deliver government secrets?

And yet, Hitchcock and screenwriter Ernest Lehman craft such a FUN screenplay with just ENOUGH plausibility that we let it go. The movie is a blast. The adventure is supreme. We still get lost in the movie and go on the journey.

Eve Marie Saint and Cary Grant proving the value of “star power, style, and charisma”.

In a way, Vertigo and North by Northwest prove the validity of two kinds of moviemaking that are often at the center of moviemaker debates. Vertigo is the kind of serious art movie made in the Hollywood system that required a lot of work and a lot of pain and a lot of risk. It took its toll on many of its moviemakers (including the relationship between Jimmy Stewart and Hitchcock which never got fully repaired).

North by Northwest, in comparison, shows that a great movie can be made while everyone on it is having a blast as well. It proves Kurosawa’s point that a great movie is ALSO a “joy to create”.

Arguably the most recognizable still of all of Hitchcock’s and Grant’s bodies of work.

These movies, made back to back, serve as vital bookends to a vast library of work. They show JUST HOW MALLEABLE a genre can be. Both Vertigo and North by Northwest can arguably be called Suspense-Thrillers (Hitchcock’s bread and butter genre his entire life). Yet both are as different in story, tone, execution as if one was a foreign art house movie and one a summer blockbuster.

Craig Hammill is the founder.programmer of Secret Movie Club.