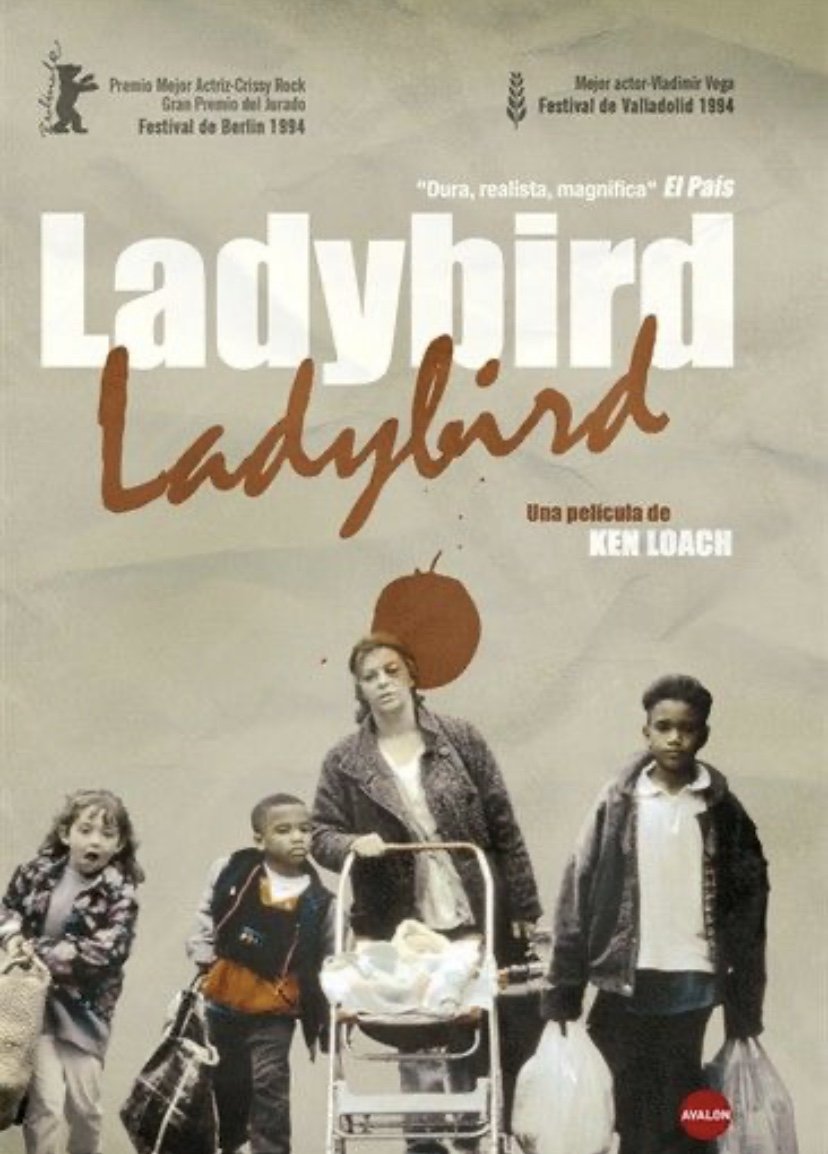

DIFFICULT PEOPLE: Ladybird, Ladybird (1994), directed by Ken Loach by Matt Olsen

A few weeks back, in discussing Wish You Were Here, I suggested that the film succeeds in no small part due to the audience’s empathy exceeding its irritation with the lead character’s self-defeating (and self-abusive) behavior. Nowhere is that dynamic in clearer display than in Ken Loach’s hyper-naturalistic, bio-drama, Ladybird, Ladybird, based on real subjects and stories from the distressed and immigrant society of 1980s London.

The film begins with the central figure, Maggie Conlan, enjoying a night out with friends, singing “I Never Promised You a Rose Garden” – which, in retrospect, must be interpreted as an entirely appropriate theme song but also a massively understated bit of exposition / foreshadowing. In this introduction, Maggie, gives the impression of an even-keeled woman in her mid-thirties. She’s White, probably working class, and not free from worry but not crippled by it either. Another patron at the bar, Jorge, a Paraguayan exile, approaches her and a tentative attraction develops between the two as they share their histories. Through flashbacks, Maggie is revealed to have experienced a significant trauma in the recent past; she’s been declared a negligent mother by the state and her four children have been placed in foster care.

What’s most interesting here is that, it’s incontrovertibly true that Maggie’s behavior has caused her children harm and the actions taken by Social Services, while painful and extreme, are arguably warranted. The System is not inherently the Bad Guy in this story. As a solution, it’s not ideal but, as a temporary measure, it could potentially be an effective method of keeping the children safe while their parent works toward bettering their situation. However, Maggie carries the weight of a volcanic temper. The path she is expected to navigate is an impossibility of frustration and, to her, a personal indignation. Her entire nature, forged by her own pain, cannot comply with the expectations asked.

The role of Maggie Conlan was played here, in her first film appearance, by a fairly successful and well-known stand-up comedian from the UK confusingly named Crissy Rock. (Her career began and achieved prominence nearly simultaneously with Chris Rock’s.) As a debut performance, it’s astonishing. As a performance by anyone of any professional standing whatsoever, it’s astonishing. The success of a film rests on all of its contributors and components, of course, but even the most equitably-minded would be hard pressed to deny her impact. The fullness of character she achieves is staggering and undeniably 100% necessary for the film to function. If the audience doesn’t feel the humanity beneath her ultra-defensive, violent exterior there’s nothing to care about.

To the film’s great merit, the goodness within Maggie is never laid on thick. In fact, it’s almost invisible – only really present in the cumulation of a few scattered moments where she is able to demonstrate caring and capability. There’s a sequence toward the latter third where Maggie makes an effort to “pull it together” and present herself as a changed person – steady, reliable – in an effort to regain her children. There’s no big makeover or rehearsal and when the meeting happens it’s not presented as an overt display of contrition. She’s heartbreakingly placid. What makes it so effective is the understanding the audience brings to the scene. Because we know that she’s putting on a performance – telling a lie – and nothing has really changed, it’s an ultimately futile act of submission.

For I assume many of us, an encounter with Maggie (or someone like her) in real life would be a daunting test of one’s patience. It’s so difficult, for me at least, to respond to this kind of manic, aggressive personality with kindness. By showing the totality of the human here, Ladybird, Ladybird forces an audience into empathy and dares the viewer to translate that feeling to the world at large.

Matt Olsen is a largely unemployed part-time writer and even more part-time commercial actor living once again in Seattle after escaping from Los Angeles like Kurt Russell in that movie about the guy who escapes from Los Angeles.